On Respect and Wonder of All God’s Security Cameras

- Mark Coleman

- Aug 22, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 23, 2020

Our children are our future and deserve our attention and our “best selves” to show up and support them, even if we don’t have all the answers. The truth is, none of us do. But if our children can have the courage and intellect to put us to the test, we must be there willingly and without judgement, to listen, care, and guide. Perhaps, in the humility and art of a simple conversation to a complex question, we can learn something about ourselves, our true nature, and our life’s future that can help us attain a higher purpose, if we choose to allow it to.

From parenting to politics, we should all be held to the highest standard

Although the role of parent comes with new responsibilities and unexpected surprises, it can be, should we choose to accept the mission, one of the most rewarding experiences of one’s life. As a parent of two boys, now ages ten and twelve, I find myself in a constant state of self-reflection (self-redirection), learning (realizing I know less and less every day), and personal growth (becoming more mindful and less irritable).

You might think that after a decade of parenting I should have accumulated by now, at least 10,000+ hours of guided and meaningful experiences with my boys to make me a parenting expert (per Malcolm Gladwell), earned my honorary doctorate in child psychology, or at a minimum, be a Lego master builder. Sure, like many other parents, I have strong credentials in critical services like on-demand tech support and ‘Generation Z and Alpha’ linguistics, having recently discovered bridge language between Pokemon, Fortnite, and Star Wars. But by all accounts, I’m an imperfect human and subsequently, an imperfect parent. That said, I am actively working to become better at both.

At this point of life, I’m confident and comfortable in saying that I frequently learn more [about myself and the continued unveiling of life’s purpose] from my boys [and family] than I do from anywhere else. About a week ago, during a car ride to escape the monotony of a home-based summer vacation, my oldest son casually asked, “hey dad, what if animals were God’s security cameras?” Not expecting the question, let alone the intrinsic intrigue and wisdom it immediately beckoned, I giggled and asked my son, “that’s interesting, what do you mean?” My son replied, “well, what if animals like dogs or deer, fish or cows, or any other animals were like God’s security cameras here on earth, watching and recording us. What if God kept an eye on us through animals and nature?”

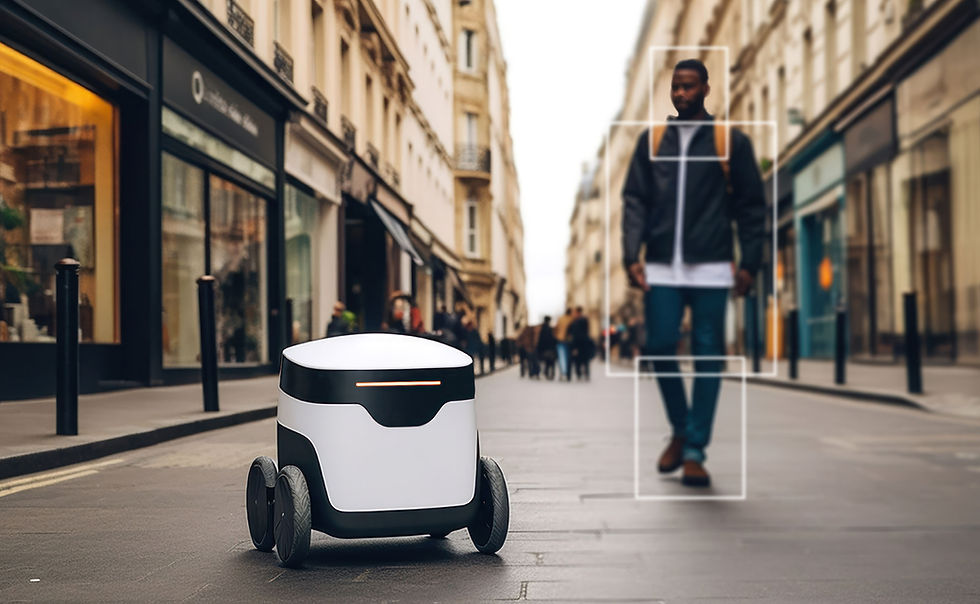

His question, whether he realized it or not (likely not), was multilayered and multifaceted, provoking a great deal of cerebral stimulation. Just the weekend before we visited the Rochester Zoo, one of our first outings in a long while. I thought that perhaps the experience may have sprung my son’s question into focus. For some reason my brain also shifted to DARPA and the insect surveillance (cyborg bugs) programs they’ve worked on. The connotation of “God’s eye,” the surveillance economy which we now live in, and questions on ethics, privacy, and freedom all surfaced. My mind also jumped to thinking about the divine transcendence in all nature and living things, a belief held by many cultures and indigenous peoples.

Character is what you do, and who you are, when no one and everyone is watching

This latter thought is what I find the most consequential. The adage, “what you [we] do when you [we] think no one is watching,” speaks directly to our character and integrity. No one wants to feel as if they are being watched with out their consent (i.e., the perception and threat of a surveillance state). There are, however, billions of people worldwide that believe in a God or divine spirit that is the creator of life and who works through all living things. Obtaining concrete statistics and facts on this statement are difficult because the belief in God can vary across cultures, geographies, and languages. Prior research and studies by Gallup, Pew Research, and even the CIA have estimated that greater than 80% of the world’s population identifies with a formal religion. However, identification with a formal religion is not a good predictor of whether a follower or practitioner of the religion believes in God. According to Pew Research, in the U.S., the percentage of people identifying themselves with a formal religion has been declining. Interestingly however, Pew Research has also found that the percentage of people that believe in God or another “higher power or spiritual force,” has been increasing.

I reference these studies not to prove or disprove anything, but to add context to an idea that a vast majority of people have, whether through social and environmental conditioning, religious and cultural assimilation, or through a deep sense of human knowledge and knowing (which cuts across our genetic, physiological, conscious and subconscious spiritual-physical being) that there is a higher power, force or spirit that overlooks humanity. While we seek to understand and unlock the true origins of life, there remains great mystery and many unanswered questions, let alone questions we have yet dared to ask.

This is why I found my son’s question, “what if animals were God’s security cameras?,” fascinating. If we value life, and treat life with dignity and respect, one intrinsically believes in something more than themselves. Whether that is a higher power, God, or something else is relevant, but it is not [necessarily] the essential point. Rather, dignity for life stems from within, a fundamental and grounded belief that we should be benevolent to all living things as a basic virtue of character represented by our actions in the here and now, as well as a demonstration of our faith in that we are part of a universal ecosystem, enriched by each other, working together to advance the future of all life. In this way, we are not separate (as humans) from physical nature or spiritual forces, rather we are intimately entwined in a cycle of rejuvenation and recreation.

Ultimately we have to be the honest stewards and trust brokers of our existence

I gently gripped the wheel and thought about how best to reply. I reflected on my son’s age, what might be on his mind, what he might be absorbing from what’s happening in the world around him. I dug deep into the folds of my brain, looking for a file folder that said, “God, mortality and other tough existential questions children ask other than sex.” I couldn’t find the file folder. It must have been corrupted or possibly removed. Regardless, I cannot recall the last time I had my hard drive backed up.

So, I floated between some other files, references and subjects like ethics, philosophy, environmental studies, sociology, earth science, psychology, and literature. I didn’t want to over intellectualize a response to my son, and quite frankly, the situation did not warrant a deep discussion per-se. But his question was, in my mind, profound. It was only appropriate to engage my son in a conversation commensurate with his inquiry and interest. So, we chatted for a few minutes and I quickly realized, without him knowing it, that he was teaching me.

My son’s inherent ability to assimilate what we might view as abstractions of reality into a specific question that set off a contemplative “dad and son” discussion of right versus wrong, morals versus principles, and beliefs versus values was unexpected but met with admiration. My son is interpreting the world around him in ways that are unique to his personality and approach to deconstructing fact from fiction, truth from reality. He is learning, maturing, and growing into his self. The process, sometimes awkward and other times unnerving is ultimately beautiful.

If we believe God is watching, then he is. In asking my son’s question a different way, we begin to reveal more about the knowledge, wisdom, and higher sense of unity that we all possess. If animals are God’s security cameras, what images, sounds, and picture do they record and tell of humanity? Do they feature our actions in our best light and intentions? Do they show us behaving compassionately and with dignity? Or do they represent humans as an apathetic, ill-tempered, and destructive force? When I think about it this way, I’m personally concerned about how we’d be viewed in the eyes of a higher power.

This moment requires more from all of us, for the sake of our children's future as well as our own...

Our youth are also watching, listening, and learning. They are conduits to a future that we are defining today. What we say, how we say it, what we do (and don’t do) by way of our intentions and actions are all shaping our future today. In the past 90-days alone, a cascade of challenges have impacted the U.S. and the world, including the COVID pandemic and public health crisis, the significant downturn of the economy, pervasive racial justice and inequality, and increased political and civil unrest.

This is not a political commentary. A divisive, demeaning, and destructive rhetoric and culture of behavior has overtaken and overshadowed more rational and productive discourse of society in recent weeks. To address the plethora of challenges at our doorstep today, we must seek unity and lead across all facets of life, with compassion, patience, and decisive dignity. To prepare for an uncertain future and prevent the continuation of racial and social injustice, we must change how we are perceived and how we are accepted, by our youth in this very moment. We have to be the change we want to see carried forward by the next generation.

Our children are our future and deserve our attention and our “best selves” to show up and support them, even if we don’t have all the answers. The truth is, none of us do. But if our children can have the courage and intellect to put us to the test, we must be there willingly and without judgement, to listen, care, and guide. Perhaps, in the humility and art of a simple conversation to a complex question, we can learn something about ourselves, our true nature, and our life’s future that can help us attain a higher purpose, if we choose to allow it to.

Comentarios